A research paper on the driverless car

This paper provides an empirical study that shows how Google's driverless car is framed in the media and evaluated in the public through a content analysis. Based on the media's framing, a strategy is recommended, which aims to manage potential issues associated with the driverless car.

INTRODUCTION

Technology has become a vital part of our everyday lives. Emerging technologies as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and process automation are created to help our societies, transform the way our companies do business and improve our overall quality of life (Cearley, 2016). The development is exponential and somewhat inevitable. In fact, we are witnessing a global transformation that is characterized by both digital, physical and biological technologies, which are not only transforming the world around us, but also the very idea of what it means to be human (World Economic Forum, 2016). With lines of business in robotics, intelligent housing and even internet-beaming solar drones (Google, 2017), Google is a frontrunner in this new transformation. In 2009 the software giant announced the next leap for mankind: A fully autonomous vehicle. In 2016 the self-driving car project evolved into a tech company called Waymo (Waymo, 2017). The technology is presented as a movement with the aim of saving millions of lives that are lost in traffic every year (Ibid.). Although the technology has the potential to evolve mobility, a radical change in the automobile industry may divide the public opinion and could potentially harm Google’s reputation due to the ethical and safety related risks associated with the technology. The American professor in Public Relations and Issue Management, Timothy Coombs, believe that “the best way to manage a crisis is to prevent one” (Coombs, 2015: 31). Although Google is in no crisis as of now, proactive issue management is necessary in order to detect potential issues and create a fundament for a successful product launch. This leads us to the paper’s research question:

How is the driverless car, Waymo, portrayed by selected media and the public, and which strategic communicative actions can Google take in order to legitimize their product?

Thus, the academic relevance of this research paper lies within issue management and the importance of monitoring the external environment when a new, society-changing product is to enter the market. This paper provides an empirical study that shows how the driverless car is framed in the media and evaluated in the public through a content analysis. Based on the media’s framing, the paper will suggest an overall strategy, which aims to both manage potential issues associated with the driverless technology and legitimize the product. Additionally, the paper delimitates to the US market, as this where Google aims to launch its driverless car.

Theoretical Framework

With the context and research question in place, it is possible to define the core theoretical concepts and sub-research questions that are needed to analyze this case.

Organizational legitimacy

One of the driving forces in corporate communication is organizations’ quest for legitimacy (Christensen et al., 2008: 14). The term has various definitions in institutional literature, but one of its founding fathers, the sociologist Mark Suchman, defines legitimacy as: “… a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions.” (Suchman, 1995: 574; Bunduchi, 2014: 2; Phillips, 2003: 29).

Therefore, legitimacy not only affects the way stakeholders engage with the organization, but also how they understand and trust the organization, and it goes far beyond the organization acting according to law, as it is a perception owned by its stakeholders (Suchman, 1995; Schultz-Jørgensen, 2014: 173). With the impact of globalization, organizations are faced with new communication technologies and a more educated stakeholder landscape than ever before (Christensen et al., 2008: 18). Thus managing legitimacy is crucial for an organization’s future license to operate (Patriotta et al., 2011), and this is especially relevant when it comes to distributive new technology, such as Google’s (Bunduchi, 2014). In continuation of this, there are three different types of legitimacy: Pragmatic, moral and cognitive (Suchman, 1995: 577).

Pragmatic legitimacy is founded on an exchange relationship between the organization and its stakeholders (ibid.: 578). This form of legitimacy is governed by self-interest from the organization’s stakeholders, as their support relies heavily on what value they can derive from the cooperation. Moral legitimacy is based on the stakeholders’ perception of organizational activities as either good or bad. The stakeholders evaluate whether the organization’s activities are “the right thing to do” (ibid.: 579). The cognitive legitimacy revolves around the organization’s ability to create meaning for its stakeholders (ibid.: 582). Where pragmatic and moral legitimacy can be obtained by simply engaging with stakeholders (Bunduchi, 2014: 8), cognitive legitimacy is a far more fixed perception – a “taken for grantedness” – of organizational activities. This makes it the strongest, but also the hardest, form to obtain (Suchman, 1995: 583).

Although organizational legitimacy extends far beyond managerial decisions from an institutional perspective (Christensen et al., 2008: 16; Suchman, 1995: 576; Patriotta et al., 2011: 1805), this research paper will take a more strategic approach to the term, thus seeing legitimacy as something managers can in fact control in order to attain the 5 desired perception among the organization’s stakeholders (Phillips, 2012). When faced with legitimacy issues, organizations can use strategies to either gain, maintain or repair organizational legitimacy (Suchman, 1995: 600). More recent scholars have supplemented this notion and suggest that discourses and rhetoric play a vital role in the strategies (Patriotta et al., 2011: 1807). Furthermore, legitimacy-building activities include lobbying, gathering feedback and building internal relations (Bunduchi, 2014: 8). The different legitimacy forms and strategies will be used as strategic recommendations after a thorough analysis of Waymo’s situation as framed by the media.

Agenda setting

In order to analyze, how the media portrays Waymo, this research paper draws upon agenda setting theory as presented by Carroll and McCombs (2003).

An agenda consists of different objects that we may have an opinion about, for instance public issues, companies or institutions (Carroll & McCombs, 2003: 37; McCombs & Ghanem, 2001: 68; Schultz et al., 2012: 98). Agenda setting happens when the media places an issue or another object on the public agenda, and this will influence the public opinion (Carroll & McCoombs, 2003: 41). While the media can focus news coverage on some matters related to the organization, it may choose to ignore others (Carroll & McCoombs, 2003: 41; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007: 11). This makes agenda setting especially important to the organization, as the media can increase pressure on the organization to deal with an issue (Cornelissen, 2017: 193).

In dealing with agenda setting, we work with three different levels:

First and second level of agenda setting

The first level of agenda setting revolves around the salience of objects in the media. Even though most agenda setting research is concerned with public issues, corporate actors are an important object to address as well (Carroll & McCombs, 2003: 38). The public uses the media’s input to decide, which issues and actors are important, and the more salience and coverage they get by the media, the more it influences the public opinion (Carroll & McCombs, 2003: 37; Cornelissen, 2017: 158).

The second level of agenda setting relates to an object's attributes, which can be described as the overall tone or evaluation of an object (Carroll & McCombs, 2003: 37). Thus the media not only play a role in delivering information about an object, it also plays a vital role in assessing and presenting reputation to the public. Reputation scholar David Deephouse argues that an organization’s reputation is based on these evaluations in the media (2000: 1097). Furthermore, the evaluation itself is made by 6 rating each media unit as either favorable, neutral or unfavorable (Ibid.). This leads us to the following sub-research questions:

SRQ 1: Which issues and actors are salient in the media and in the public in relation to Waymo?

SRQ 2: Which evaluations are made about Waymo in the media and in the public?

Third level of agenda setting

The third level of agenda setting is also referred to as framing. Robert Entman (1993) originally defined framing as: “… to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.” (Entman, 1993: 52). Thus framing is based on the assumption that issues can be put into a specific frame that aims to control how an issue is discussed (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007: 11).

Kirk Hallahan (1999: 207) argues that framing is, in fact, a strong tool in constructing reality, because certain aspects are highlighted while others are left out. Although Hallahan views framing strategies within the field of crisis management, framing can still be useful to public relation practitioners in terms of locating underlying issues, their cause and who is understood to be responsible (Hallahan, 1999: 229). This leads us to the next sub-research question:

SRQ 3: How is Waymo framed in the media?

Because the media agenda influences the public agenda (Carroll & McCombs, 2003), an organization’s public relations activities must be aimed towards setting the media agenda. This notion is also referred to as agenda building. Agenda building happens when the organization frames certain issues in order to influence the media agenda (Hallahan, 1999: 218). Bearing in mind that legitimacy is vital for the organization’s future license to operate, especially when it comes to new technology, we can formulate the next sub-research question:

SRQ 4: How should Google frame potential issues in its external communication in order to gain, maintain or repair legitimacy towards its key stakeholders?

Issue Management

In order to recommend an overall strategy to combat potential issues, we need to draw upon theory of issue management. Initially, an issue was defined as “… an unsettled matter, which is ready for decision.” (Chase, 1984). However, recent definitions emphasize a more long-termed managerial discipline: ”… a public concern about the organization’s decisions and operations that may or may not also involve a point of conflict in opinions and judgments regarding those decisions and operations.” (Cornelissen, 2017: 192). At its core, an issue is a type of problem whose resolution can impact the organization (Coombs, 2015: 32). Furthermore, issues can be categorized into four different stages: Latent, active, intense and crisis (Cornelissen, 2017: 193). In the latent stage, the issue is no threat to the organization, as generally the public is more positive or just unaware of its existence (ibid.). When the issue becomes more salient as a result of media attention it reaches an active stage. This is followed by the intense stage, which has the potential to evolve into a crisis (ibid.).

Today, the field of issue management is a growing area of activity within corporate communication (Cornelissen, 2017: 191; Jaques, 2012: 40), and issue management can be defined as the identification of issues and actions taken to affect them (Heath, 1990). Failing to handle an emerging issue that has been set on the agenda by the media can be fatal, as was the case for British Petroleum in 2010 (Kleinnijenhuis et al., 2013). Thus issue management is an ongoing process with a focus on early, proactive identification of threatening issues that could escalate into a crisis (Jaques, 2012: 38; Coombs, 2015: 31). This process consists of three major phases: Environmental scanning, issue identification & analysis and issue-specific response strategies (Cornelissen, 2017). As agenda setting theory will cover the first two phases, this paper will put emphasis on issue-specific response strategies: Buffering, bridging, and advocacy (ibid.: 198). A buffering strategy is about delaying the development of an issue by remaining silent or postponing decisions regarding the issue (ibid.). On the contrary, bridging is when the organization recognizes the issue as something inevitable and adapts its activities to external expectations. Finally, an advocacy strategy seeks to change the opinions of stakeholders on the issue (ibid.: 198). This leads us to the final sub-research question:

SRQ 5: Which issue management strategy should Google use going forward?

Methodology

Generally, this research paper uses a social constructivist approach in which reality is constructed through interaction in a social system (Fuglsang & Olsen, 2004). This means that the role of communication is a constructing one. When the media makes an issue more salient in the minds of the public, they are indeed constructing reality. As public relations practitioners we aim towards managing the perception of stakeholders, and the consequence of this is that the media, with its choice of framing, can affect the corporate communication of organizations. With this overall notion in mind, we can move on to the collection and analysis of data.

Data collection

This paper’s data collecting method is based on a qualitative content analysis, which is a systematic method used to analyze and categorize elements of text. The opposite approach, the quantitative, uses predefined measures such as word count with a semantic “closedness”. This was to be avoided, as the aim was to make the data collection as consistent as possible so that another researcher would be able to reach the same results. Therefore, the qualitative approach, which implies an iterative refinement of categories and units, was selected.

Overall, this paper follows Krippendorf’s framework (2004) for the content analysis (see Appendix A). Before going into the analysis of the data, a brief description of the data collection process using this framework is needed.

Context: As stated earlier, the context of this research paper is that Google is to launch a product that could divide the public opinion and harm its legitimacy. The unit of analysis, therefore, needed to correlate with this context.

Research question: The question in hand then became to discover the main issues, actors, and framing of both media and public in order to provide strategic recommendations for the organization.

Text: To answer the research question this paper has looked at different text inputs. The texts selected came from two primary outlets representing the media and the public: Newspapers and comments on social media. Rather than looking at the organization itself, e.g. through press releases, the unit of analyses needed to give an indication of what was being said about Waymo.

Sampling: In the actual execution of the content analysis, sampling was used to find the right data to analyze. Based on specific terms, which will be explained in the next section, a large amount of content was selected for thorough analysis, while everything irrelevant was left out of account.

Coding: Potter and Levine-Donnerstein (1999) argue that researchers must use clear theory to guide the design of the coding scheme, as it will otherwise affect the reliability and validity of the coded data. Therefore, the selected material was thoroughly analyzed and put into specific categories depending on the different levels of agenda setting theory: 1. Actors and Issues, 2. positive, negative and neutral evaluations and 3. attributes related to the cause, solution, and consequence.

Reducing: After analyzing the material through coding, the text was reduced in order to make sense of it and find specific tendencies and strategic implications.

Answer: Based on the strategic implications from the data, it was possible to develop a set of communicative recommendations for Waymo.

With the overall approach to data collection described, we can go into detail and elaborate on the considerations regarding the types of media used in the content analysis: Newspapers and comments on social media.

Newspapers

78 news articles were chosen in order to see, how the media portrayed Google Waymo. The data, in the form of news coverage, was collected from the 7th of April 2016 until the 25th of May 2017. One of the largest news and media databases in Denmark, Infomedia, was used to collect the data. The search results were limited to the organization by using the following search strings: Google Waymo; Waymo; Google driverless car.

Through this paper’s focus on the US market, it was chosen to leave out all Danish media in order to decrease the amount of second-hand interpretation. For instance, it was found out that major Danish media, such as Berlingske or DR, often just redirected to articles from the US. Therefore, newspapers from the US were primarily used, because the papers have a large, countrywide reach. Recent circulation figures show that papers such as USA Today, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal have a combined daily reach of approximately 6 million people (Cision, 2014), which makes these important media to address. Furthermore, these newspapers were 10 combined with international and technology-minded media such as Wired or Auto car UK, as this allowed a broader and more varied perception. For the full selection of media used, see below graphs that shows the number of different articles from content analysis as well as different media platforms used in the content analysis.

Comments on Social Media

A total of 805 comments were gathered to estimate the opinion of the public. To get the broadest result possible four different social media channels were selected: Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube. The comments from these channels were found in the same period of time as the newspapers. See below table for an overview of social media channels, content and comments analyzed.

When collecting data on social media, however, there are potential sources of error. For instance, it is suggested that the medium actually matters more than the message communicated (Schultz et al., 2011), which means that Google's use of each medium has different implications. The paper will elaborate further on these implications in the results section. Moreover, the comments on social media are by no means written exclusively by people from the USA, which harms the validity of this paper's delimitation to the American market.

A survey might have been used, but since consumers of the American market would be more complicated to reach through the forums available, this paper instead looks at comments on social media. A survey on Danish forums would have been less representative and further harm the validity of the data.

Data analysis

In order to analyze how Waymo was portrayed by the selected media and in the public, the different articles were coded to detect the most salient issues and actors, how these actors were evaluated and finally the cause, solution, and consequences of the driverless technology.

In order to address the first level of agenda setting 8 issues and 10 actors were mapped out based on a number of samples. Examples of such issues are “Safety”, “Legal requirements” and “Price”, while actors are “Consumers”, “The Government” and “Car manufacturers”.

To look at the second level of agenda setting, the approach of Deephouse (2010) was used to give each data material a number: 1 (positive), 0 (neutral) and -1 (negative). This gave an indication of both the media evaluation of the issue and the tone of actors mentioned.

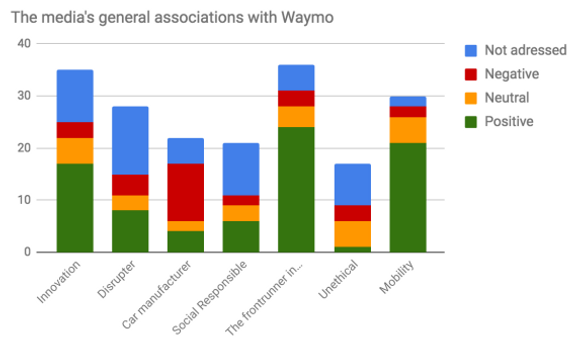

To analyze the third level of agenda setting this paper categorized each actor’s association with the driverless technology as being either part of the cause (1), responsible for the solution (2) or responsible for the consequences (3). Although Deephouse (2010) suggests that this categorization is used in crisis management, it is used in this case of issue management, because it allows us to estimate how the media frames specific issues. Finally, sampling was used to estimate the media’s more general associations with Waymo such as “disruption”, “mobility” or “the frontrunner in driverless technology”.

RESULTS

First-Level agenda setting

SRQ 1: Which issues and actors are salient in the media and in the public in relation to Waymo?

Issues

In the newspapers we find three salient issues that stand out: Safety, competition and potential gaps in technology as seen in below graph of issues as portrayed by selected media.

In the media, the issue of safety relates to a consumer concern for safety in using the driverless car (Mui, 2016). This is the most salient issue, as it appears in 77% of the collected articles. Competition is the second most salient issue, which refers to major software companies such as Apple, Tesla, Lyft, and Uber or car manufacturers such as Volvo, GM or Ford, who also invest heavily in the driverless technology (Levin & Harris, 2017; Strohm, 2015). The issue of potential gaps in technology is perceived as something more internal, for instance the car’s disability to foresee “bad drivers” in traffic, its maneuverability under heavy weather conditions or the risk of the car being hacked (Loiseau, 2017).

Other, less salient issues, include the predicted high price of the driverless car or Waymo’s internal resources, which is understood as tangible and intangible resources, or lack thereof (Gardner, 2016). Broader external issues are legal requirements such as the laws and regulations surrounding the car, or the infrastructure, which refers to the availability of a physical structure for transportation. Finally, the issue of shared economy refers to the market’s maturity towards ride sharing services. Looking at the social media landscape other issues become apparent as seen in below graph showing issues portrayed by the public through comments on social media.

Interestingly, issues in the public mind have a clear consumer-oriented nature, as they relate to price of the driverless car, the looks of the car, how driverless technology might take away the driving experience and how it may substitute human labor. The most 12 salient issues, however, is still the concern for safety, with a total of 210 mentions, and the gaps in the technology, with a total of 163 mentions, which implies that these particular issues are vital to manage. I have summed up all the issues in a SWOT to give them internal and external dimensions.

Actors

Below graph displays the number of mentions of relevant actors in the news media. The most salient actor by far is Google, which this research paper defines as the umbrella corporation Alphabet, the software organization Google and the tech company Waymo as well as the driverless car by the same name. Besides Google, the main actors presented in the news articles are the potential consumers, competitors and car manufacturers, who have a combined salience of 152 mentions out of the total 299. Other actors include NGOs, the US government, Waymo’s suppliers, its engineers, the North American Auto International Show and Education Institutions such as Harvard.

In the comments on social media, the public is actually responding to content from Google through status updates, videos or hashtags, which again makes Waymo the most salient actor.

Second-level agenda setting

SRQ 2: Which evaluations are made about Waymo in the media and in the public?

The immediate result of the content analysis is that the main part of the issues is evaluated more negatively than positively in the media, which is displayed the graph below. Especially gaps in technology (with a negative to positive ratio of 20-6) and competitors (with a 26-7 ratio) stands out as very negatively evaluated issues.

Looking into the data, however, we actually see a different result. Below graph shows the evaluation (-1 = negative, 0 = neutral, 1 = positive) of Waymo over time in news media. Due to aggregated media evaluation, some data exceeds the range of -1 to +1. Although most issues are evaluated negatively, the aggregated data shows that there are in fact large neutral and positive parts of the evaluation in the media across time. This could indicate that the driverless car is still under development, which makes information about the finished product harder to attain by the media. Several articles therefore take a very informative and neutral stand on the issues in hand: “Google parent Alphabet on Tuesday spun off its self-driving car project from the “moonshots” unit into its own company, a strong step toward commercializing the technology” (Baron, 2016); ”It’s hard to say for sure when 13 autonomous vehicles will become mainstream” (Kerstetter, 2017); ”The company now reports that test drivers only have to take control about once every 5,000 miles.” (Randazzo, 2017).

When looking at two of the most salient issues, i.e. safety and gaps in technology, we see that these are still evaluated negatively by the media over time (below graph). Safety has 20 negative evaluations out of 56 mentions, while gaps in technology has 21 negative out of 43. That is to say in 41% of the cases, these salient issues are evaluated negatively, which calls for careful issue management.

In the public, evaluations are also very mixed, as seen in below graph with evaluations of Waymo based on comments from various social media channels. While 240 out of the 430 comments on YouTube are negative, larger parts of comments on twitter are neutral, while comments on Facebook and LinkedIn are positive overall. People on Facebook and LinkedIn are responding to Waymo’s content with congratulating remarks, with admiration for the innovative work and its possibilities, while comments on YouTube are questioning the implications of the technology. This evaluation gap may indicate a difference in the relation to each medium. For instance, the tweets on twitter are short, informative statements that are passed on from news media, which make them more inclined to be neutral. Additionally, Waymo’s Facebook-followers have proactively chosen to follow its journey, which makes them more likely to be positive, while viewers on YouTube, who could be exposed to video content by chance, are without this biased opinion. Hence the medium actually matters more than the message (Schultz et al., 2011).

Although these issues have had plenty of media attention, both the public and the media are generally very neutral in their evaluation of different issues related to Waymo. The large part of neutral evaluations indicates that the driverless technology is still very new and most people do not yet have a formed opinion on it. This means that many of the issues facing Waymo are still in the latent phase (see model below). As the model indicates, only the most salient issues have become active in the public domain through agenda setting. The strategic implication of the latent issue phase is that the organization is still very much able to affect the public opinion with agenda building. Communication initiatives should therefore be aimed towards sensemaking Waymo’s identity and the car (Kjærgaard et al., 2011; Weick, 1988), because it is still quite hard for the public to grasp.

Third-level agenda setting

SRQ 3: How is Waymo framed in the media?

With the second level of agenda setting completed we can move on to looking at the actors’ associations as either responsible for the cause, solution or consequence of the driverless technology.

The graph below shows the media’s associations with Waymo as either the cause, solution or consequence of the driverless technology over time. Waymo is primarily viewed as responsible for the cause of the driverless technology, as 36 out of 78 articles holds the organization accountable.

The closest actor, that is responsible for the cause, is the competing companies (e.g. Lyft, Apple or Uber) with 20 articles, as shown in the graph below. While Waymo and the car manufacturers (e.g. Ford, Honda or Volvo) are seen as part of the solution, with a total of 44 articles, it is the consumers who are most associated with the consequences of the technology.

The content analysis enable a further look into the actual essence of the issues and more specifically, which frames appear in the media landscape. Four dominant frames emerge: The inability frame, the savior frame, the affordability frame and the exploitability frame.

The inability frame

This frame relates to both the issues of gaps in technology and safety, because the overall discourse created in the media, that the car is flawed when interacting in real world traffic, is likely to influence the perception of the car as safe. The inability frame brings up the ethical dilemma of machine learning, because Waymo might be unable to choose between harming either people in traffic or its passengers. According to researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, this implies that the algorithm controlling Waymo will need to embed moral principles that guide the car in situations of unavoidable harm (Greenemeier, 2016). Furthermore, Waymo may fall short when navigating in traffic with unpredictable human drivers. The media frames this as an important concern in the technology: “Even if driverless cars can learn to interact with human-driven cars, human drivers will not be able to deal with driverless cars. The resulting confusion would lead to more accidents and congestion, rather than less.” (Mui, 2016). This frame is based on the actual testing of the car until this point: “Typically, the accidents involved either distracted or anxious humans rear-ending the Google cars at a stop light at walking speeds.” (Goodman, 2016). As mentioned, the main part of the media frames Waymo as responsible for the solution, but it is also suggested that the US government must determine what aspects of the car are safe only after it becomes more integrated into public life (Cava, 2017). Going back to the 15 point of Carroll and McCombs (2003), that the media’s agenda setting influences the public opinion, this notion is indeed supported in the public: “I’m not getting in that thing”; “It might be kinda weird that we’re trusting robots with our lives now…”; “Curious to see what happens when the accidents begin”.

The savior frame

At the same time, Waymo is framed as part of the solution to a bigger problem in society, namely that people are getting killed in traffic. It is estimated that 35.000 people die in car accidents in the US each year and a survey from US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that human error is the critical reason for 93% of crashes (Randazzo, 2017; Silver, 2017; Levin & Harris, 2017). The media frames Waymo as a major opportunity in this regard: ”Driverless cars, which promise to see better and react faster than humans while never getting sleepy, drunk or distracted, offer the possibility of dramatically reducing driver error and the resultant human suffering.” (Mui, 2016). This frame is also very much mirrored in the public, for instance on Facebook: ”Bring it on. It’s the easiest way to save 40.000 lives a year, billions in car repairs and tens of billions in medical costs.” (Appendix O).

The affordability frame

Another major concern, as framed by the media, is the affordability of the product. Several articles question the innovation, as it is useless if not within an affordable price range: “The cost of sophisticated electronics, including lidar, radar, sensors, cameras, computing and networking devices, on top of the cost of additional development, maintenance, and liability, will price driverless cars out of reach of most consumers.” (Mui, 2016). Google has sought to combat this threat by engaging in partnerships with car manufacturers such as Honda or Fiat Chrysler, which resulted in the 100 Pacifica Hybrid Minivan (Lippert & Butters, 2016; Vlasic, 2017). The solution has attracted criticism as well, because the minivan is estimated to cost magnitudes more than an average minivan (Loiseau, 2017), and comments on YouTube show that potential consumers are very much aware of the products high price.

The exploitability frame

The media also highlight the associated risk in the car having more control units, lines of code and wireless connections, which makes it an exposed target for hackers. Andy Birnie, a system-engineering manager at NXP semiconductors elaborates: “A hacker can potentially take control of the car, through exploitation of a weakness, and could cause the vehicle to refuse to start or to crash, or it could exploit the privacy of the driver, and (their) data, including financial information.” (Silver, 2017). Cyber security relates to the salient issue of gaps in technology, and the media view Waymo as responsible for the cause, while consumers are associated with the consequence. For 16 instance, if the driverless car were to become a vehicle of precision bomb delivery (Mui, 2016).

Thus, Waymo is primarily framed in a negative way by the media. It can be concluded that the most salient issues, related to cause, solution and consequence of the driverless technology, have been transferred by the media onto the public agenda.

STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS

Sub-research question 4: How should Google frame potential issues in its external communication in order to gain, maintain or repair legitimacy?

As previously mentioned the main part of the issues portrayed by the media is neutral, thus in the latent phase. The frames of inability, affordability, and exploitability have, however, the potential to damage Waymo’s organizational legitimacy. While Google might have obtained large amounts of cognitive legitimacy, as they are subconsciously seen as a global leader in software and IT, it is hard to imagine that the company Waymo, which was founded only in 2016, has the same amount of taken-forgranted society acceptance. This implies that Waymo must gain legitimacy on its own (Suchman, 1995: 586), and the cognitive form is thus difficult to obtain. Official statements from the website emphasize how the product is to drive global mobility forward, while CEO, John Krafcik, states: "We're not about building better cars, we are about building better drivers" (Streitfeld, 2017; Waymo, 2017). This suggests that Waymo's legitimacy form is not based on pragmatic self-interest either. The moral legitimacy form is both founded on the public's normative evaluations of the organization and embedded in a broader social context, which makes it the most applicable form. When the media frames Waymo as "saving lives" it is indeed based on the moral evaluation of the organization's activities as either good or bad (Suchman, 1995).

Gaining moral legitimacy

Due to the nature of the media framing, as an explicit moral discourse, it is recommended to use a moral reasoning strategy, because this strategy is prosocial of nature and seeks to align organizational interest with the expectations of stakeholders to gain legitimacy (Scherer et al., 2012: 264). In this way, Waymo will gain legitimacy by engaging in open dialogue with key stakeholder groups with the aim of reaching consensus. Waymo could for instance initiate dialogue about the issue of safety with the US government, its competitors and other car manufacturers in order to create a sensible framework for standardized regulation. “The Self-driving car Coalition for Safer Streets” is an example of such work (Self-driving Coalition, 2017).

The goal for Waymo in its agenda building activities is to persuade corporate stakeholders of the moral and economical value that the driverless car can bring to society. Combatting the issue of gaps in technology, the organization could use the savior frame to reinforce the associated savings in medical cost, which would be a result of decreased accidents on the roads. These solid, organizational results are moreover a key factor in what drives moral legitimacy (Suchman, 1995: 588). Besides the overall frame of society wealth, Waymo must frame the technology as driving mobility forward and as something that makes the individual more productive, as it saves us time when traveling. Supporting lobbying activities should attempt to create legislation that will help the public to perceive the driverless technology as the next step in mobility, i.e. making it more appropriate in the social system of norms and values (ibid.: 574).

Furthermore, it is recommended that Waymo reinforce the moral strategy by participating in external relational building and obtaining feedback from stakeholders, as this too gains moral legitimacy (Bunduchi, 2014: 7). Relational building activities may come in partnerships with car manufacturers, such as the recent deal with Fiat Chrysler (Vlasic, 2017). Besides helping Waymo to change the perception of the technology, as something safe and socially acceptable, partnerships with large brands will allow the company to strengthen its position in the market, as Waymo lack the intangible resources and sales infrastructure of the well-established car manufacturers. The company must obtain feedback from its stakeholders by making sure that professional communities, for instance of engineers, recognize the product’s performance and conform the driverless car to some degree of standards. This tactic will further combat the issue of the gaps in technology. An important addition in this regard is the constant product testing, which has seen Waymo rise above its competition, as it has driven 635,868 miles compared to the combined 20,286 miles of all its competitors (Mui, 2017). This is something the organization should emphasize in its external communication.

Sub-research question 5: Which issue management strategy should Google use going forward?

With an overall strategy for gaining moral legitimacy, it is possible to recommend a more specific issue management strategy for Waymo. By using the position-importance matrix, the stakeholders from the first level of agenda setting can be prioritized accordingly.

While the content analysis show that consumers, competitors and car manufacturers are the most salient actors mentioned in the media, the matrix analysis indicates that these are not the most vital to address, because competitors and car manufacturers actually supports Waymo. Therefore the primary actors to address are the consumers, NGOs, and the government. These actors are more important to Waymo, because the government for instance holds major legitimate and regulatory power over the car, while consumers can simply chose not to buy it. Even though these groups may not necessarily oppose on the issue of safety as of now, they a crucial to address, because of this power.

The most salient issues – competitors, safety, and gaps in technology – are important to address. While safety and the gaps in technology are related to attitudes and therefore seen as something that can be changed with PR initiatives and communication, the issue of competition is something of a more strategic nature. As public relation practitioners, we are not as concerned with how internal resources and capabilities are turned into a competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). Thus, the two main issues to address in the strategy are safety and gaps in technology. Moreover, these issues are interdependent, because the perceived gaps in the technology lead consumers to feel unsafe with the product.

Advocacy as an issue-specific response strategy

As Waymo need to establish an opinion in latent publics and seek to make an actual change in opinion in others, an advocacy strategy is recommended. This strategy correlates with the objective of gaining moral legitimacy, as it aims to persuade external stakeholders that Waymo’s position on the issue of safety is both rationally acceptable and morally legitimate (Cornelissen, 2017: 198).

Studies in consumer behavior suggest that people find it easier to form an opinion only after engaging with the brand (Winchester, 2008). Addressing the issue of safety, it is therefore recommended to involve the consumers in a set of events. Michelle Krebs, an executive analyst at Autotrader, thinks that Waymo’s new Early Rider program will be a vital factor in this regard: “… the key to acceptance of self-driving cars is exposure and education… it’s smart for Waymo to invite the public to take its self-driving Chrysler Pacifica Hybrid for a spin to build confidence in their technology.” (Carva, 2017).

With their “VT4 framework of organizational news content”, Carroll and Deephouse (2014) propose five different content dimensions, which are important to organizations. One of these isolated types of content, Ties, relates very much to the third level of agenda setting, as it refers to the linkages the news media make to the organization and 19 another topic (ibid.: 86). This notion is important for Waymo, because the organization need to establish strong ties to the product category of driverless technology in order to form a strong opinion in the public. Therefore, a proactive campaign must seek to sensemake the driverless car, establish these associations and generate the future expectations of the consumer, as it is hard to imagine that consumers will buy something they do not understand. A mass media campaign targeting consumers could focus on the salient issues and combat the inability frame by educating the consumer and by using key messages such as Waymo’s progress on real roads, the multiple cities the car is stationed in or the millions of miles it has already driven (Waymo, 2017).

Moreover it is crucial that Waymo bargain for the support of advocacy networks, because these can help them to change the policies of governments through influential networks. The American NGO, Conscious Capitalism, for instance states: “We believe that business is good because it creates value, it is ethical because it is based on voluntary exchange, it is noble because it can elevate our existence and it is heroic because it lifts people out of poverty and creates prosperity” (Conscious Capitalism, 2017). With the support of such an NGO, Waymo is better suited to build an agenda and influence government officials. It is equally wise to embed in institutions, such as NGOs, because it allows Waymo to gain more moral legitimacy (Suchman, 1995: 600). As mentioned, Waymo could seek the cooperation of opinion leaders in the automobile industry, as these are a powerful force in different communities. John Quelch, professor of marketing at Harvard Business School, suggest that the opinion leaders are also vital in reaching critical mass on the US market: “With any innovation there is a group of opinion leaders and early adopters who will set the stage and enable the concept to reach critical mass” (Millward, 2017).

Furthermore, the content analysis shows that the media associates Waymo with mobility and as being a frontrunner in driverless technology.

This suggests that Waymo could potentially become a thought leader, and it is recommended to supplement the advocacy strategy with this strategy. This implies that Waymo commits itself to progressively change the issues at hand, as the moral reasoning strategy also entail, and the CEO is an important figure in this regard (Cornelissen, 2017: 199). Combatting the media frame of affordability, Krafcik, has stated: “Today, we’ve brought down that cost by 90 percent… This is a big step in making this technology affordable and more accessible to millions of people". (Vlasic, 2017). The vertical integration of its sensor system suppliers is just a small step, but one that needs to be communicated thoroughly nonetheless.

CONCLUSION

This research paper has investigated how Waymo is portrayed by selected media and in the public in order to recommend an overall strategy for issues management and product legitimization. Based on a qualitative content analysis, this paper has found that safety, competition and potential gaps in technology are the most salient issues, as portrayed by the media, while this notion is supported by comments on social media. Key actors found in the media landscape include the potential consumers of the driverless car, competitors such as Uber and car manufacturers. While the most salient issues are evaluated negatively, the large part of issues are actually neutral, which indicates that the driverless technology is still very new, without a formed opinion and very much in the latent issue phase. The active issues of safety and gaps in technology are, however, on the public agenda due to media agenda setting. Furthermore, the media frames Waymo negatively overall using frames such as an inability frame that primarily sees the organization as part of the cause of driverless technology. Therefore, it is recommended to use a moral reasoning strategy in order to gain moral legitimacy by engaging in open dialogue with stakeholders, participating in external relational building, obtaining stakeholder feedback and delivering concrete, organizational results. Moreover, it is recommended to use an issue-specific response strategy based on advocacy, which should be aimed towards consumers, NGOs and the US government and focus on the issues of safety and gaps in technology. Waymo could involve potential customers in events to build up confidence in the technology and educate latent publics in the benefits of the car, while partnerships with NGOs and influential opinion leaders will act as strong tactics in the proactive issues management strategy.

LITERATURE

Research papers

Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage, Journey of Management, Vol. 17 (1), pp. 99-120.

Bunduchi, R. (2014). Strategic and institutional approaches to product innovation: peripheral product innovation and the challenge of organisational legitimacy, paper presented at 21st Euroma Conference, Palermo, Italy, 20/06/14 - 25/06/14.

Carroll, C. E., & Deephouse, D. L. (2014). The Foundations of a Theory Explaining Organizational News: The VT4 Framework of Organizational News Content and Five Levels of Content Production. In J. Pallas, L. Strannegård, & S. Jonsson, Organizations and the Media: Organizing in a Mediatized World. Routledge.

Carroll, C. E., & McCombs, M. (2003). Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public's images and opinions about major corporations, Corporate Reputation Review, Vol. 6 (1), pp. 36–46.

Deephouse, D. L. (2000). Media Reputation as a Strategic Resource: An Integration of Mass Communication and Resource-Based Theories. Journal of Management, pp. 1091–1112.

Entman (1993): Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm, Journal of Communication, Vol. 43(4), pp. 51-58.

Hallahan, K. (1999). Seven Models of Framing: Implications for Public Relations. Journal of Public Relations Research. Vol. 11(3), pp. 205-242.

Heath, R. L. (1990): Corporate issues management: Theoretical underpinnings and research foundations.

Jaques, T. (2012): Is issue management evolving or progressing towards extinction?, Public Communication Review, Vol. 2 (1), pp. 35-44.

Kjærgaard, A., Morsing, M., & Ravasi, D. (2011). Mediating Identity: A Study of Media Influence on Organizational Identity Construction in a Celebrity Firm. Journal of Management Studies, 48(3), 514- 543.

Kleinnijenhuis, J., Schultz, F., Utz, S., & Oegema, D. (2013). The mediating role of the news in the BP oil spill crisis 2010: How US news is influenced by public relations and in turn affects public awareness, foreign news and the share price, Communication Research (42), pp. 408-428.

McCombs, M., & Ghanem, S. I. (2001). The convergence of agenda setting and framing, Framing public life: Perspectives on media and our understanding of the social world. USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Patriotta, G., Gond, J.P., & Schultz, F. (2011). Maintaining legitimacy: Controversies, orders of worth, and public justifications. Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 48 (8), pp. 1804-1836.

Phillips (2003): Stakerholder legitimacy, Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 13 (1), pp. 25-41.

Potter, W. J. & Levine-Donnerstein, D. (1999). Rethinking Validity and Reliability in Content Analysis. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 27, 258-284.

Scheufele & Tewksbury (2007): Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models, Journal of Communication, Vol. 57, pp. 9–20.

Schrerer, A. G., Palazzo, G. & Seidl, D. (2012). Managing Legitimacy in Complex and Heterogeneous Environments: Sustainable Development in a Globalized World, Blackwell Publishing Ltd and Society for the Advancement of Management Studies

Schultz, F., Utza, S., & Göritzb, A. (2011). Is the medium the message? Perceptions of and reactions to crisis communication via twitter, blogs and traditional media. Public Relations Review (37), pp. 20-27. 22

Suchman (1995): Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches, Academy o/ Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, 571-610.

Weick, K.E. (1988). Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations. Journal of Management Studies, 25 (4), pp. 305-317.

Winchester, M., Romaniuk, J. et al. (2008). Positive and negative brand beliefs and brand defection/uptake. European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 42(5/6), pp. 553-570.

Books

Chase, W.H. (1984): Issue management: Origins of the future.

Christensen, L. T., Morsing, M. & Cheney, G. (2008). Corporate Communications: Convention, Complexity, and Critique. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks, California. Sage publications.

Coombs, W. Timothy (2015): "Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding", 4th edition, Thousand Oaks, California. Sage publications.

Cornelissen (2017): Corporate communication: A guide to Theory and Practice. 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, California. Sage publications.

Fuglsang, L., & Olsen, P. B. (2004). Videnskabsteori i samfundsvidenskaberne. 1st edition. Roskilde Universitetsforlag.

Krippendorf, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, California. Sage publications.

Schultz-Jørgensen, K. (2014): Virksomhedens omdømme, 1st edition, Gyldendal Business, København.

Articles and websites

Baron, E. (2016). Google self-driving car project steps out on its own as ‘Waymo’. The Mecury News. Visited 15/07/2017, available through: http://www.mercurynews.com/2016/12/13/google-self-driving-car-project-steps-out-on-its-ownas-waymo/

Cava, M. (2017). Google's self-driving cars are offering free rides. USA Today. Visited 17/07/2017, available through: https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/news/2017/04/25/googleself-driving-cars-finally-take-passengers/100861240/

Cava, M. (2017). Google's self-driving car unit to stop shaming humans. USA Today. Visited 17/07/2017, available through: https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/talkingtech/2017/01/19/waymo-blog-stop-shaminghumans/96797988/

Cearley, D. (2016). Gartner's Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2017. Forbes. Visited 12/05/2017, available through: https://www.forbes.com/sites/gartnergroup/2016/10/26/gartnerstop-10-strategic-technology-trends-for-2017/#6efcec9186b3

Cision (2014). Top US daily Newspapers. Cision. Visited 03/08/2017, available through: http://www.cision.com/us/2014/06/top-10-us-daily-newspapers/

Conscious Capitalism (2017). Corporate Website. Conscious Capitalism. Visited 05/08/2017, available through: https://www.consciouscapitalism.org/

Gardner, G. (2016). 8 big challenges remain for self-driving car makers. USA Today. Visited 17/07/2017, available through: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/cars/2016/09/21/eight-big-challenges-remain-selfdriving-car-makers/90791782/

Goodman, E. (2016). Self-driving cars: overlooking data privacy is a car crash waiting to happen. The Guardian. Visited 25/07/2017, available through: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/08/self-driving-car-legislation-drones-datasecurity

Google (2017). Corporate Website. Google. Visited 12/05/2017, available through: https://www.google.com/intl/en/about/

Greenemeier, L. (2016). Driverless Cars Will Face Moral Dilemmas. Scientific American. Visited 18/07/2017, available through: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/driverless-cars-willface-moral-dilemmas/

Kerstetter, J. (2017). Daily Report: More Self-Driving Cars Take to the Streets. The New York Times. Visited 15/07/2017, available through: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/25/technology/daily-report-more-self-driving-cars-take-to-thestreets.html?_r=1 Levin,

S. & Harris, M. (2017). The road ahead: self-driving cars on the brink of a revolution in California. The Guardian. Visited 18/07/2017, available through: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/mar/17/self-driving-cars-california-regulationgoogle-uber-tesla

Lippert, J. & Butters, J. (2016). Honda in Talks With Google’s Waymo on Self-Drive Tech. Bloomberg Technology. Visited the 13/07/2017, available through: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-12-21/honda-in-talks-on-self-driving-technologywith-google-s-waymo

Loiseau, J. (2017). The 5 Biggest Challenges to the Driverless Car Revolution. The Motley Fool. Visited 02/07/2017, available through: https://www.fool.com/investing/2017/03/11/the-5-biggest-challenges-to-the-driverless-carrev.aspx

Millward, D. (2017). How Ford will create a new generation of driverless cars. The Telegraph. Visited 05/08/2017, available through: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2017/02/27/ford-seeks-pioneer-new-generation-driverless- 24 cars/

Mui, C. (2017). Waymo Is Crushing The Field In Driverless Cars. Forbes. Visited 05/07/2017, available through: https://www.forbes.com/sites/chunkamui/2017/02/08/waymo-is-crushingit/#e20c372aa9f4

Mui, C. (2016). 7 Ways Driverless Cars Could Fail. Forbes. Visited 05/07/2017, available through: https://www.forbes.com/sites/chunkamui/2016/04/08/7-driverless-doomsdays/#7355e83516cf

Mui, C. (2016). 7 Wonders of the Driverless Future. Linkedin (Blog). Visited 05/07/2017, available through: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/7-wonders-driverless-future-chunka-mui

Randazzo, A. (2017). Waymo's self-driving cars need less driver intervention. USA Today. Visited 20/07/2017, available through: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/cars/2017/01/13/waymos-self-driving-cars-need-lessdriver-intervention/96529888/ Self-driving

Coaltion (2017). Corporate Website. Self-driving coalition for safer streets. Visited 08/08/2017, available through: http://www.selfdrivingcoalition.org/

Silver, J. (2017). Twelve things you need to know about driverless cars. The Guardian. Visited 17/08/2017, available through: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jan/15/driverlesscars-12-things-you-need-to-know

Streitfeld, D. (2017). Waymo to Offer Phoenix Area Access to Self-Driving Cars. The New York Times. Visited 17/07/2017, available through: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/25/technology/waymo-to-offer-phoenix-area-access-to-selfdriving-cars.html

Strohm, M. (2015). Driverless cars: 6 firms on the cutting edge. Bankrate. Visited 17/07/2017, available through: http://www.bankrate.com/auto/6-firms-that-are-testing-driverlesscars/#slide=5

Vlasic, B. (2017). Detroit Auto Show Reveals a Google-Designed Van That Could Steer the Industry. The New York Times. Visited 18/07/2017, available through: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/08/business/google-waymo-self-driving-minivan-fiatchrysler.html

Waymo (2017). Corporate Website. Waymo. Visited 12/05/2017, available through: https://waymo.com/

World Economic Forum (2016). Global Information Technology Report. Edits by Baller, S., Dutta, S. and Lanvin, B. Available through: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GITR2016/WEF_GITR_Full_Report.pdf